ANTIQUITIES.

By Francis Joseph Bigger and William J. Fennell.

-- -- -- -- --

PREHISTORIC REMAINS.

THE north-east of Ireland is particularly strong in prehistoric remains. Carns, pillar-stones, cromleacs, stone circles abound in every district; but we do not purpose to give any lengthened or systematic account of them, only a general sketch of what may be observed.

CARNS.

Almost all the high mountains have been crowned with carns, many of which have, however, in recent years been removed. The group of carns on the Slieve Croob, near Ballynahinch, are perhaps the most important, whilst others on Slieve-a-true, near Carrickfergus, and on Carn-eigh-aneigh, between Cushendall and Ballycastle, Carn-an-truagh on Knocklayde at Ballycastle, are amongst the most important. The latter is said to mark the grave of three princesses.

Of standing stones, those of Standing Stone Hill, near Dundrod, and in Culfeightrin churchyard at Ballycastle, and one at Loughbricland, are typical examples. There is also one of the largest on the old road between Newry and Rathfriland, known as the "Long Stone." These are, perhaps, the most common of our ancient monuments.

Of hole stones, the best one is in the demesne near the village of Doagh, in the county of Antrim.

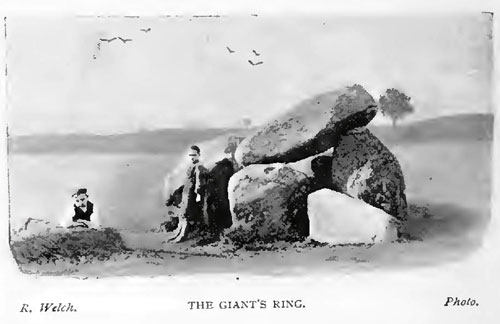

Cromleacs are also fairly numerous, a good example occurring in the centre of the Giant's Ring, near Belfast. This is a place well worth visiting at any time, being one of the finest prehistoric monuments in the north of Ireland. The rath is of most imposing dimensions, being about 600 feet in diameter, the encircling earth rampart being 80 feet wide at the base. The cromleac occupies the centre of this great ring, and was formerly surrounded by standing stones.

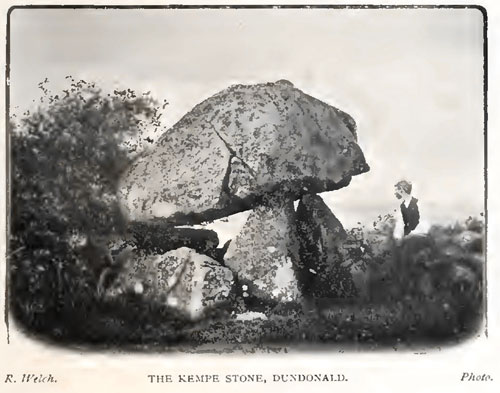

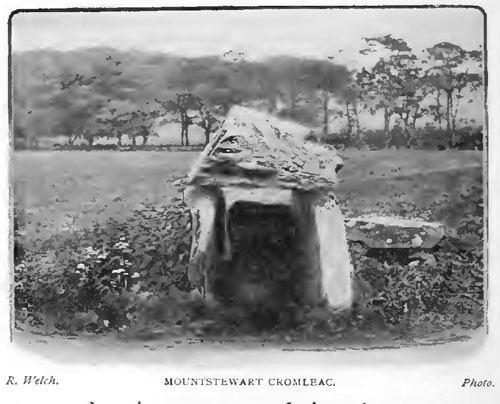

There are several cromleacs near Ballintoy on the north coast, and also one at Finvoy, underneath which urns were found; there are also two others at Ticloy. One of the best and most easily reached is in Island Magee, close to Larne Ferry, in the neighbourhood of which gold ornaments were discovered. At Dundonald, near the city, there is a fine example; and at Mountstewart there is quite a perfect little cromleac, which was at one time covered by a carn.

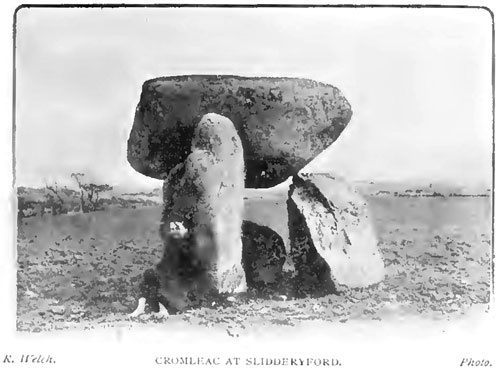

A large number of urns were found around this monument. There are other examples at Loughmoney, on Slieve-na-griddle, and at Slidderyford, near Dundrum; whilst one of the finest, both in height and in the size of the covering stone, is at Legananny, five miles from Castlewellan.

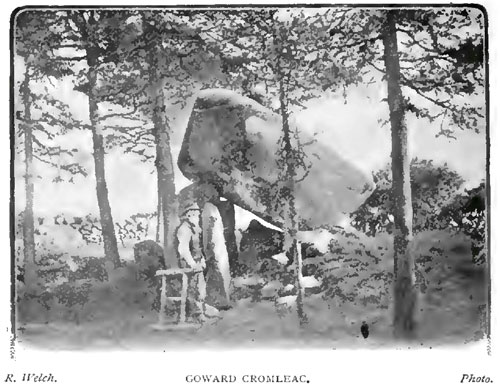

The largest of the local cromleacs is one at Goward, in the parish of Clonduff, consisting of a block of granite 13 feet long, 10 feet wide, and 3 feet thick, weighing about 50 tons, and resting on a group of nine others. Here urns have been found. It was at one time surrounded by a circle of stones. Numerous other examples occur about the district. F. J. B.

Kiste-vaens are also fairly numerous, the one nearest the city being at The Roughfort, consisting of about forty large stones covering a chamber about 40 feet long, covered by nine of the largest blocks, the end one forming what would be considered a fair cromleac. Other examples occur at Ballyhome, known as Gig-ma-gog's Grave, between Coleraine and Bushmills; one above Murlough, Ballycastle, known as Gallow-glass Grave; and one at Ballyboley, on the road between Ballynure and Larne. There is also one at Killowen, not far from Rostrevor, and another at Kilkeel. 248

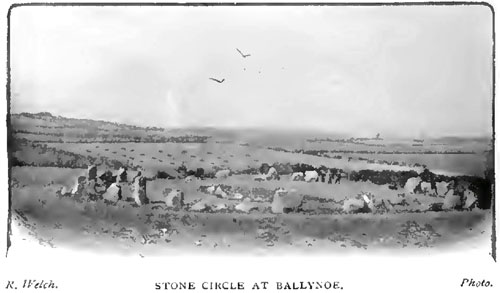

Stone circles are to be found at Ticloy, Parkgate, and Kilmakee, both the latter near Templepatrick; and also at Lubitavish, near Cushendall, where there is a group of thirty-four stones, known as Ossian's Grave. At Ballyalton, near Downpatrick, there is a circle, with an approaching avenue of stones; whilst at Ballynoe, in the same district, the best of the local stone circles is to be found. It consists of two circles, the inner about 20 yards in diameter, having twenty-two stones, and the outer about 25 yards in diameter, with about fifty stones, some of them standing 7 or 8 feet high. There are also other stones around in different positions.

F. J. B.

ARTIFICIAL CAVES, OR SOUTERRAINS.

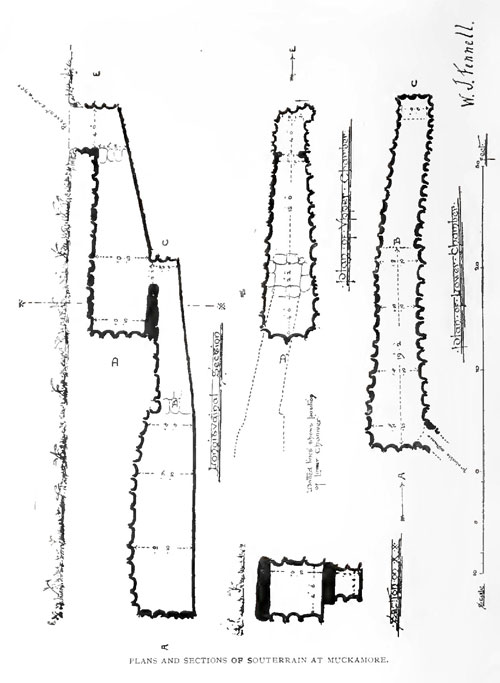

These structures may be regarded as the residences and retreats of one of the primitive races who inhabited this country. No two of them are alike in plan, but all have a general resemblance to one another in their mode of construction. The plan generally consists of chambers approached by long irregular passages, sometimes straight, sometimes zigzag, and often containing minor passages branching from the main one; these passages vary from 2 feet wide to 3 feet, seldom more; and the heights range from 2 feet 6 inches to 6 feet; while the chambers, shaped like beehives, swell out to greater areas and more lofty domes. The entrances to these chambers are protected by barriers, sometimes single, and often double, and even triple, rendering invasion an impossibility when a determined foe with a weapon was there to resist. The chambers vary in length up to 20 feet, but the passages often extend to over 100 feet. In every case these dwellings are built of rough unhewn stones, frequently of boulders, with an incline inwards towards the top, where they are covered with large flat stones, and in most cases they appear to have been built first and then covered over with earth. Often there are sewer-like passages leading to the surface which may have served for the circulation of air, and their outlets were carefully concealed or rendered unattractive from their positions. These dwellings are profusely scattered over both counties, and are found in most unexpected places -- often in forts or raths, in which case the flue runs to the outer side of the sloping bank of the rath. One of the nearest to Belfast, easily approached and entered, is on a farm at Bog Head, on the Six-mile Water, in the Grange of Muckamore, near the town of Antrim. This souterrain has the singular peculiarity of being two-storied. It is easy of entrance, and well worth a visit.

A very fine example of a souterrain inside a fort may be inspected at Stranocum, in the grounds of W. Ford-Hutchinson, which was discovered in 1897, and is like the letter Y on plan. There is also an extensive one at Tyrella, in the county of Down, and within easy distance of Dundrum or Downpatrick.

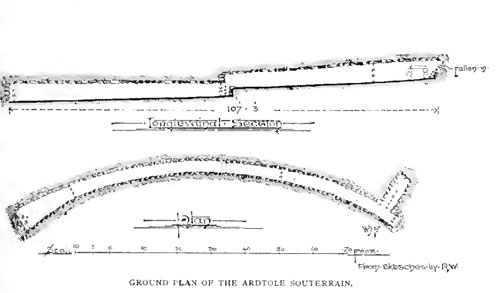

Other examples more or less difficult can be found in the county of Antrim at Holywell, Dunagore, Broughshane, Glenwherry, Toomebridge, Ballycastle, and in the county of Down at Craigavad, Downpatrick, Ardtole near Ardglass, etc., but many of them have been closed up, as they were dangerous to cattle, and a visitor may be disappointed at the end of his journey. Stone implements and bones have been found in some of them, also pottery, but they have not yet been systematically investigated.

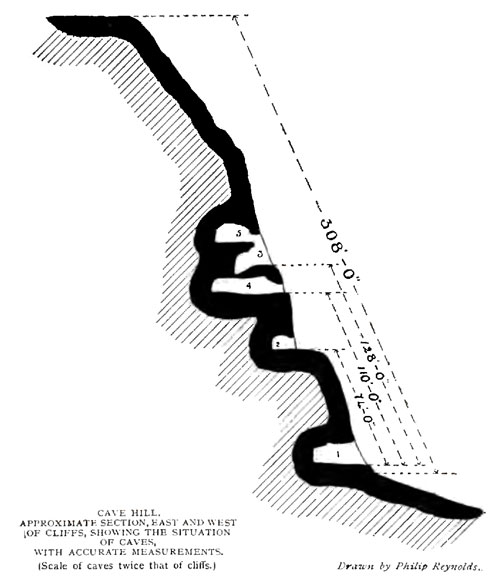

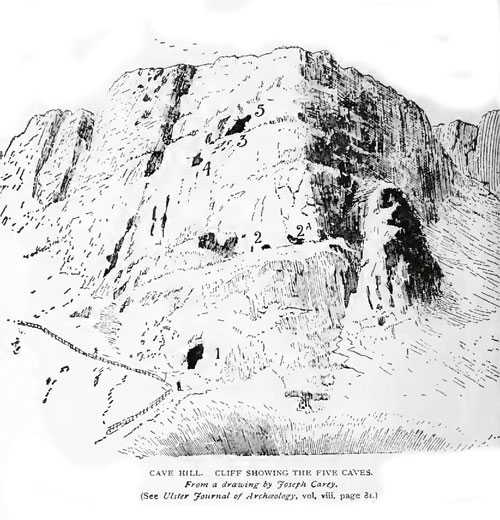

A few natural caves are to be found in the district around Belfast, which bear clear evidence of having been either artificially made or used by man. The principal ones are those on the Cave Hill, overlooking the city, and at the Knockagh, above Carrickfergus; whilst they are to be found here and there all round the coast from Belfast Lough to Portrush.

W. J. F.

From a drawing by Joseph Carey.

(See Ulster Journal of Archæology, vol. viii, page 81.)

APPROXIMATE SECTION, EAST AND WEST OF CLIFFS, SHOWING THE SITUATION OF CAVES, WITH ACCURATE MEASUREMENTS.

(Scale of caves twice that of cliffs.)

RATHS.

All varieties of earthwork are found studded over the face of the country. The largest one is at the Giant's Ring, previously mentioned; and within a short distance of it is. Farrell's Fort, a very good example. They frequently have castles or churches erected upon them of a later date. It is no uncommon thing to find an ancient fort, a mediaeval castle or church, and a modern dwelling-house or parish church close together, thus showing a long historical sequence of occupation by man in different ages.

The greatest of all the forts is Dunceltchair, or Dun-da-leth-glass, at Downpatrick, and it is rendered particularly interesting by the known history attached to it. Celtchair was one of the heroes of the Croibh-ruadh, or Red Branch Knights of the heroic period of Irish history, similar in time to the legends of King Arthur. Before De Courci's time the name was changed to Dun-da-leth-glass (the fort of the broken fetters). It subsequently gave the name, in Christian times, to the city of Ireland's patron saint, Downpatrick (Dunpatrick). Here King John stayed in 1220, and it was sacked and burned by Edward Bruce in 1316. This rath is of vast size, situated on the level banks of the River Quoyle, and has quite the appearance of a natural hill.

Rathmore, near Antrim town, was also burned by Edward Bruce; and close beside it is Rathbeg. Both of these forts are mentioned in ancient history.

Numberless forts of all known varieties -- conical, flat, round, and even square -- are to be found here, there, and everywhere over the northern counties. Emania, near Armagh, is the most celebrated, on account of its historical associations with the Red Branch Knights. Many legends circle round its extensive ramparts, and the earliest traditions are associated with its site. In many respects it is the northern Tara.

F. J. B.

CRANNOGES.

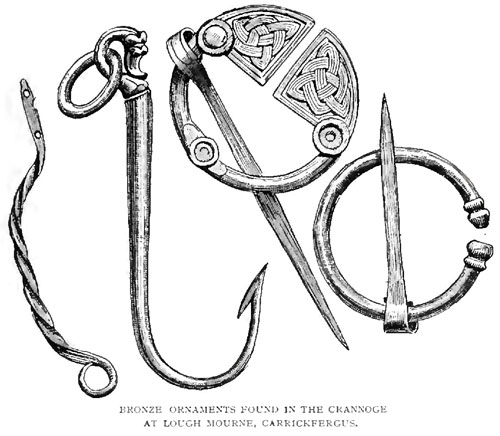

These lake dwellings are fairly numerous, and in recent years several of them have been systematically examined, with the most satisfactory results, which have been fully described in the Proceedings of the learned societies. It may be noted in passing that there is clear evidence that these residences were in occupation up till the time of Queen Elizabeth.

There are several in the neighbourhood of Ballymena, and others near Toomebridge, which have been thoroughly investigated, yielding stone, bronze, iron and wooden implements in abundance.

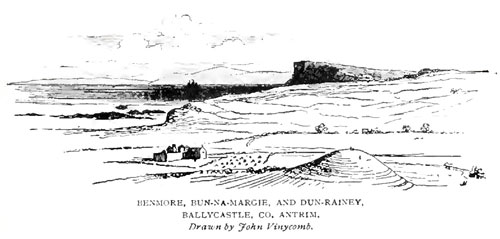

A unique example occurs in the great tarn on Benmore, near Ballycastle, being surrounded by a stone wall, with two distinct landing-places. The zig-zag paths to some of these crannoges have been discovered when the lakes were drained.

F. J. B.

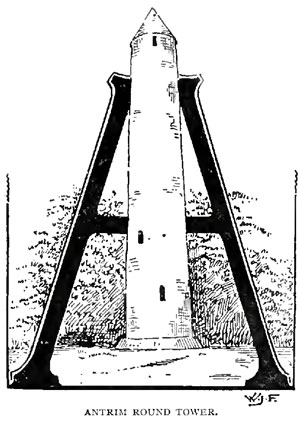

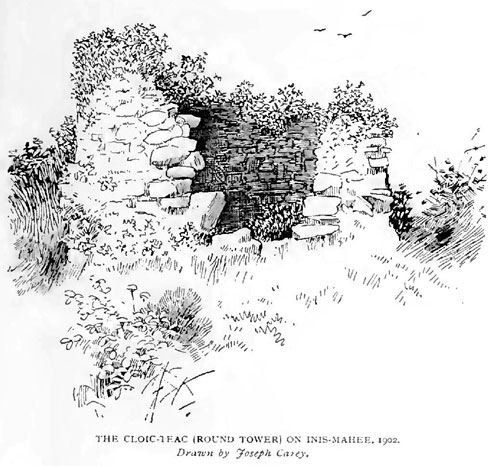

CLOIC-TEACS, OR ROUND TOWERS.

ANTRIM contains one of the most perfect round towers in Ireland, and there are remains of others at Armoy and Ram's Island, while in Down similar remains may be found at Drumbo, Maghera, and Mahee Island in Strangford Lough. These monuments are regarded as being purely national in character, unaffected by the few solitary circular towers that occur elsewhere. They possess a distinct character of their own, and a general similarity throughout Ireland, being found in almost every corner of it, and in all cases connected by evidence in stone or otherwise to the religious establishments of the early Church in Ireland; and antiquarian authorities are now fully agreed on that point, although the question of use still excites discussion.

The controversy that waged round the question of their origin was long and vexed, and many learned writers held with great tenacity to their standpoints of view from the Christian and Pagan sides. A review of the question here would be out of place, but we give in the bibliography sufficient references to satisfy the most persistent antiquary who desires further investigation.

Many of the cloic-teacs,1 like the noble one that stood beside the old abbey at Downpatrick, have been completely removed; and several of them were fast following in the same direction, but the tide of preservation came, and they were saved. The Antrim tower is one of the most perfect in Ireland, and is the solitary remnant of the ecclesiastical foundation that once flourished round it. It rises to a height of 92 feet, and has a circumference of 50 feet at the base. The doorway is well over the ground line, with inclined jambs -- a distinctive feature of the early Christian Church -- about 5 feet 6 inches high, and the ope is about 2 feet wide. The lintel-stone bears a rudely-shaped cross, but whether contemporaneous with the tower or an addition cannot be decided with certainty. The windows are at the top, and face, as is the usual custom, the points of the compass, and the stone roof is conical; so that, in nearly all respects, it is a typical example.

Margaret Stokes classified all the round towers of Ireland according to the average styles of their masonry and apertures, and that of Antrim comes under the first or earliest style; viz., "Rough field stones untouched by hammer or chisel, not rounded but fitted by their length to the curve of the wall, roughly coursed, wide jointed with 'spalds' or small stones fitted into the interstices, mortar course, unsifted sand or gravel." From this they graduated to the fourth class, in which the masonry is "closely analogous to the English-Norman masonry of the first half of the twelfth century," and the Hiberno-Romanesque ornament began to appeal, so that the range of time through which the tower building passed may have extended from the ninth till the thirteenth century. "The Belfast Museum contains a large number of skulls of persons who were buried in and about the round towers. In some cases the remains were under the foundations." See Ulster Journal of Archaeology (old series), Petrie's Round Towers, Margaret Stokes's Early Christian Art in Ireland, Vallancey's Collectanea, Round Towers by S. J., and Round Towers by O'Brien.

W. J. F.

ANCIENT CROSSES.

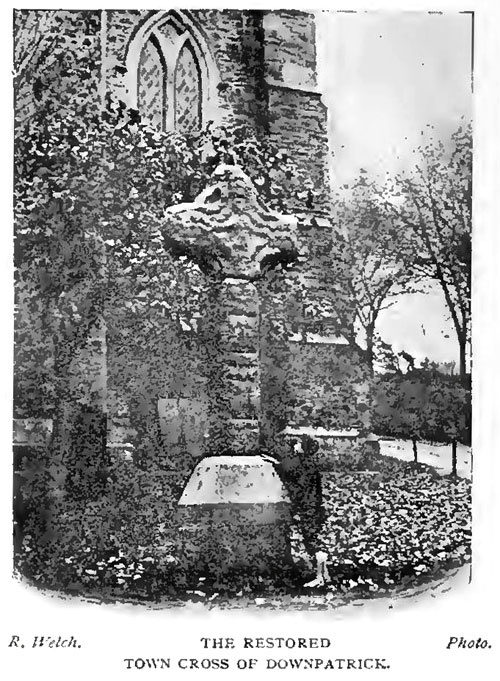

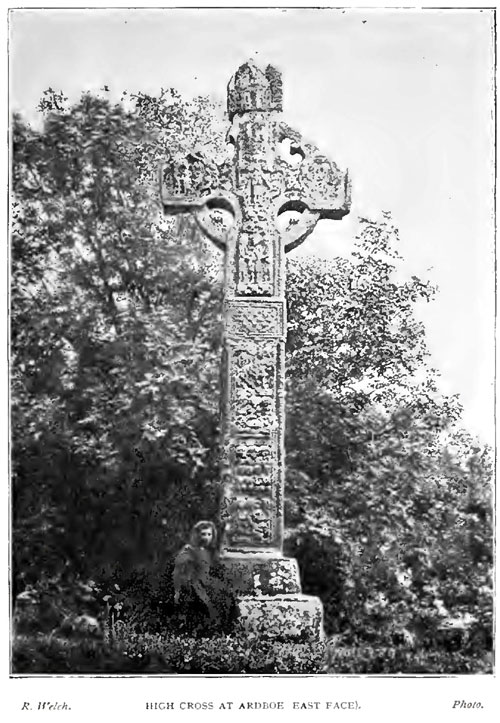

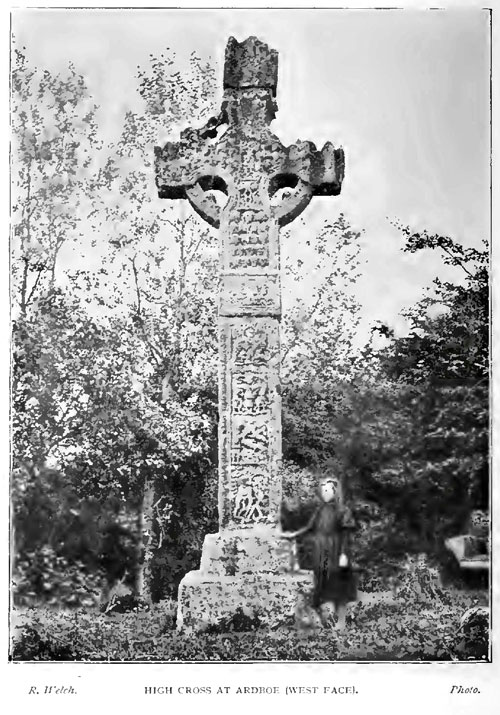

We do not possess in Ulster many examples of the sculptured crosses that form so distinguished a feature as memorials of the early Christian Church in Ireland, and whose dates may be limited to a period ranging from the tenth to the thirteenth century, but we lay claim to some vigilance for the protection and preservation of such relics as time and circumstances have brought to light. The

The ancient high cross of Downpatrick has been re-erected, the different portions being gathered together from places where they had lain in neglect for many years, and it now stands prominently before the east end of Down Cathedral. The interlacing ornament of the panels and the crucifixion can still be traced on its weather-worn face. Fragments of another cross at Downpatrick have been placed inside the cathedral for protection until the remaining pieces have been found. The cross of Dromore possesses a similar history of restoration to that of Downpatrick, as does that of Donaghmore, but is not so perfect.

The Downpatrick cross stands in the cathedral yard, facing the main street of the town. The cross of Ardboe, in the county of Tyrone, on the shores of Lough Neagh, may be considered the most important in Ulster for its size and elaborate carving. It is, however, outside the Belfast district, but easily accessible either from Cookstown or Toomebridge, and is well worthy of a visit, as it undoubtedly ranks amongst the finest of our Irish crosses. It stands i8 feet 6 inches high, and is 3 feet 6 inches across the arms, and has twenty-two panels containing sculptured scriptural subjects. (See Ulster Journal of Archaeology, N.S., vol. iv, page i, for a full description and illustrations.)

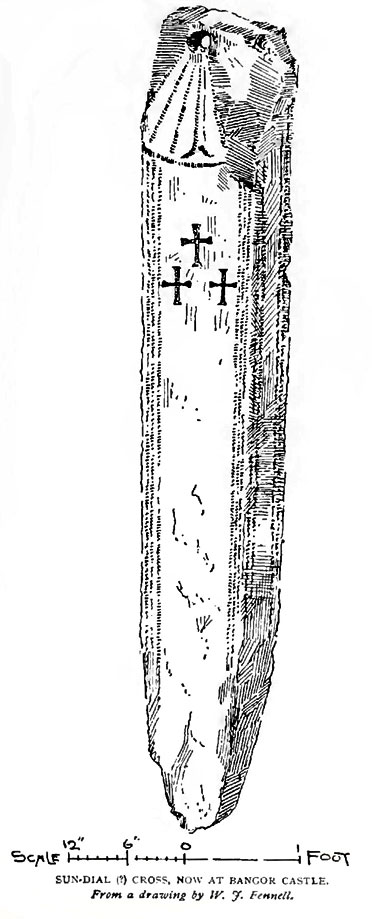

This cross has been well cared for, and is still in excellent preservation. The visitor to Ardboe should study the old churches close by this cross. Other crosses at Drumgooland, Armagh, Donaghmore, and in Tynan Abbey demesne and at Caledon are worthy of inspection. A number of rudely-cut crosses and fragmentary pieces are scattered profusely over the counties of Down and Antrim, and may be looked for at Newtownards, Bun-na-margie, Cushendun, Connor, Kilroot, Carrickfergus, Temple Astragh, Maghera, Bangor Abbey Church, etc.; but none of the elaborately-carved slabs so common at Clonmacnoise and similar places are to be found here. (See Ulster Journal of Archaeology; Early Christian Art in Ireland, by Margaret Stokes; O'Neill's Sculptured Crosses of Ancient Ireland.)

W. J. F.

SCULPTURED SLABS.

SCULPTURED SLABS.

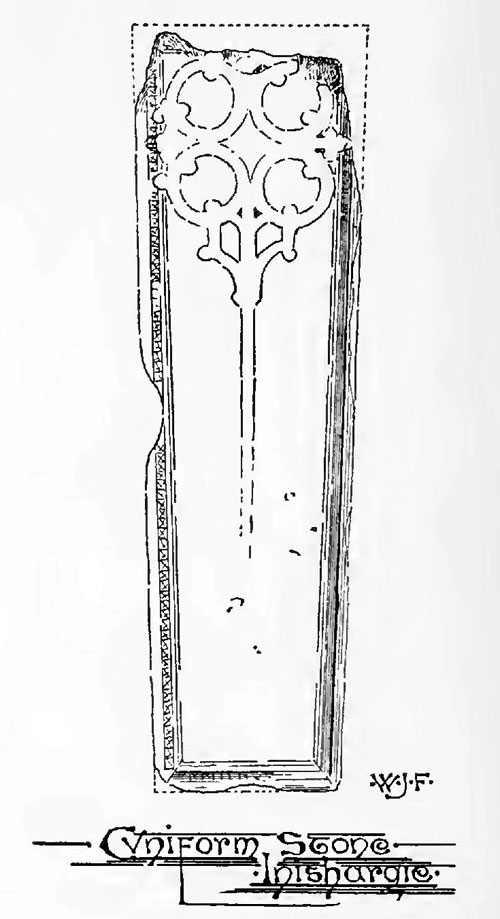

The cuneiform slabs, mostly Anglo-Norman, but some few dating from the earlier period of the Celtic Church, occur frequently throughout both Antrim and Down, and present an interesting subject of monumental study.

The richest collection in one place is in the old ruined Abbey of St. Finian, at Movilla, about a mile east of Newtownards, one of them bearing an inscription in the Irish character -- "Ordo Detrend" -- i.e., "a prayer for Detrend," who was possibly an abbot of Movilla about the end of the tenth century. This fine collection has been erected against the north wall of the church for preservation. These Norman stones are without inscriptions, but emblems are frequent and suggestive, such as leaves on the stem of the cross, as it constituted the tree of life, a chalice or pastoral staff to denote an ecclesiastic, a sword for a knight, and an old time shears or scissors to denote a woman, or, as some say, a yeoman or shearer. There are several fine cross slabs of Norman origin now well conserved in the Abbey Church of Bangor.

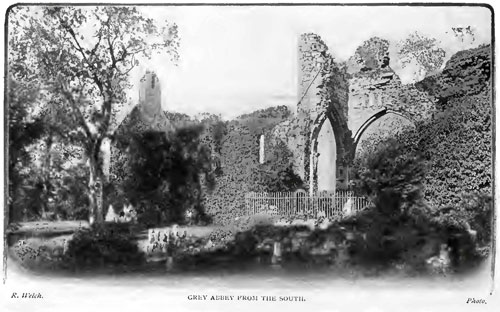

Greyabbey, in the county of Down, contains two fine slabs, one bearing the recumbent effigy of Sir John de Courci, a cross-legged warrior of the thirteenth century, while the other bears the effigy of his wife, the Lady Affreca, the foundress of the abbey.

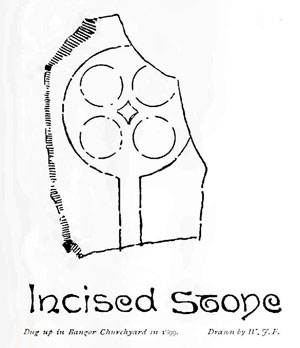

Examples of cross-inscribed stones can also be seen at Dundonald, Holywood, Maghera (Co. Down), Belfast Museum, Inishargie, Bangor, Kilroot, Carrickfergus, etc. Most of these have been illustrated in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology.

W. J. F.

ANCIENT CHURCHES.

The churches of the united dioceses of Down and Connor and Dromore should be classed under the heads of pre- and post-Reformation, and the mind of the antiquary will naturally turn to the former, although the latter have also an interest of their own. Amongst the first, the more important churches left to us are the cathedral church of Downpatrick, and the church of St. Nicholas at Carrickfergus, both within easy reach of Belfast.

The Church at Downpatrick is the cathedral of the diocese of Down, and is large, heavy, and, from an architectural point of view, not very interesting; but the old foliated capitals of the pillars are good and refined pieces of sculpture. The church was restored from ruin about 1790, and the result is what might be expected from a time when church architecture was at a low ebb. This church receives a dignity from its size and its position, crowning the summit of a hill, its lofty square tower forming an attractive landmark. Like most churches, the legend hangs round it that it occupies the site of the first Christian church, and even that of a still earlier Pagan temple. These gave place to a Benedictine abbey, dedicated to the Holy Trinity, which was founded by Sir John de Courci, who more than any other man has left his mark on the county of Down.

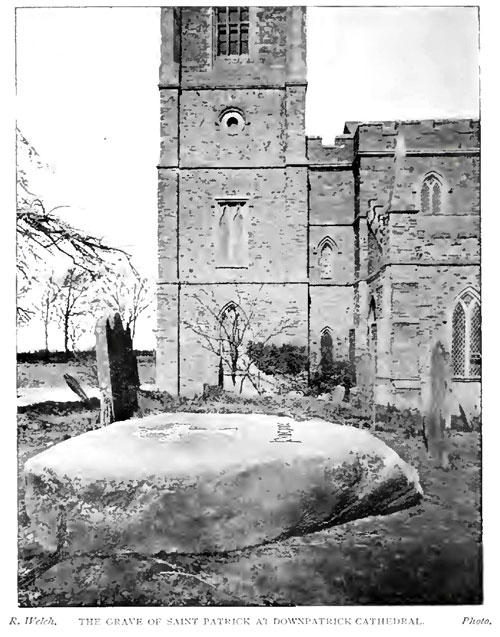

The great interest that centres round this church lies in the associations that the place has with the patron saint of Ireland, whose remains, together with those of Saints Columba and Brigid, were translated to it in 1186, "under the auspices of Sir John de Courci, and in presence of Cardinal Vivian, who had come from Rome to witness the ceremony." It is easy to understand how venerated must have been the spot that contained the relics of three such illustrious saints; but all the sanctity and love did not prevent contending foes from destroying De Courci's church, and the precise place where the saint was buried is now traditionally fixed on a spot a few yards to the south of the church; and as there is always a germ of truth in every legend, it may be regarded as fairly accurate in its location. The visitor should visit this spot, which has been recently covered with a memorial, the character of which is in keeping with that which would have suggested itself to the early fathers of the fifth century who laid the Apostle of Ireland in his grave. The incised cross and the lettering of his name are copied from coeval authorities.

This church was rebuilt according to modern ideas of Gothic art as they existed in the eighteenth century, and the remnant of the round tower was removed as unsightly and dangerous. The battle-flags of County Down regiments have been hung in this church, and should be inspected. It also contains a number of interesting monuments, including one of the Cromwell family.

Church of St. Nicholas, Carrickfergus. -- From an antiquarian point of view this church is the most interesting one in the united diocese, and is a suggestive object-lesson of how a great church -- a sister church to St. Nicholas of Galway -- possessing nave and aisles, transepts, side chapels, and all the attributes that render a church a dignified and noble structure, both reverend and attractive, can, by time and a series of successive changes, each one on the downward grade, alter the whole from the full beauty it once possessed to a much smaller and debased structure. For a complete history of these changes, we must refer the reader to the report of Sir Thomas Drew to the Diocese in 1874.

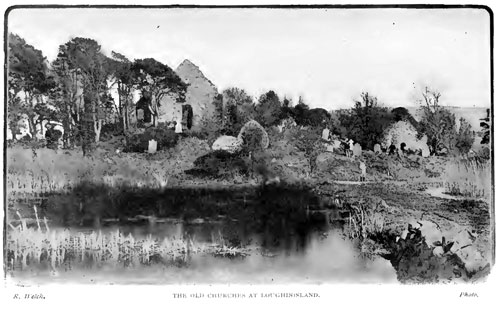

The lines of the nave arches are still traceable on the exterior of the south side. Notice should be taken of the Chichester monument, which of its kind is very fine, and records about the founder of the house of Donegall "not what he was, but what he should have been." One group of churches on Loughinisland, near Crossgar, is particularly interesting.

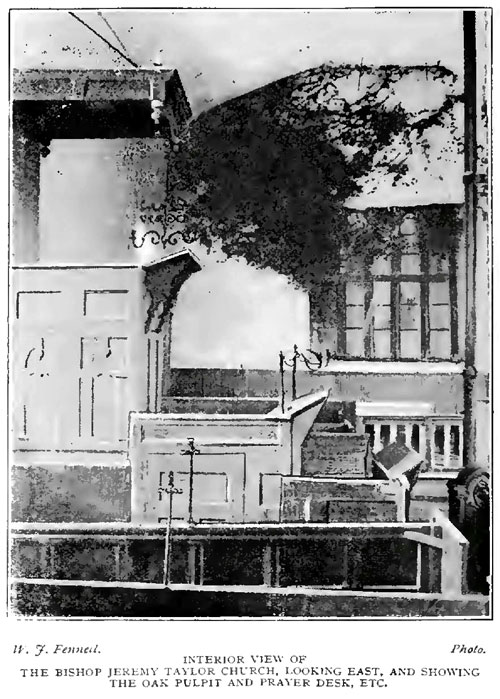

Numerous other smaller churches, their ruins or their sites, are to be found in every parish. The one, however, which will excite most admiration is the Bishop Jeremy Taylor church at Ballinderry, now completely restored. It was built at the Restoration by the learned Bishop of Down, who did not, however, live to see it completed. It was here he took refuge from the Puritans, and here many of his works were penned. The church itself is quaint and simple, with its heavy oak from the now denuded forests of Ballinderry, and its square windows. The interior still preserves all the original oak fittings, as constructed in the time of the second Charles, the old arrangements being strictly adhered to. It is well worthy of a visit.

W. J. F.

ABBEYS.

The northern counties are by no means rich in the great mediaeval structures which are found so frequently in the southern counties. What did exist have been largely swept away, or only the smallest fragments left -- often the sites alone are known.

Of Celtic foundations, that possessing one of the longest histories is, perhaps, in Nendrum, or Mahee island in Strangford Lough, fully recorded by the late Bishop Reeves. Only a few foundations and the base of a round tower now exist. Movilla, near Newtownards, was also a celebrated school of learning in the earliest ages. Several cross slabs still remain here, and a more recent church; but the great abbey of Bangor, on account of its school of learning and the many pious men it sent over all Europe, is best known. Of it, none of the very ancient structure remains, and but a few fragments of the walls of an abbey dating from Norman times, and some cross slabs, are to be found. What the northmen failed to obliterate, more modern devastators have effectually cleared away.

Of great Norman abbeys, the only one left to us having any imposing dimensions is that of Grey Abbey, beautifully situated on the shores of Strangford Lough. This was a Cistercian house, and was founded in 1193 by Affreca, wife of John de Courci, and daughter of Godfrey, king of Man.

Close to Downpatrick are the remains of Inch Abbey, which must also have been a very extensive house; but the choir alone remains, of considerable beauty, with its long lancet windows.

At Newtownards, the nave of what was a fair-sized Dominican abbey still remains. It was long used as a parish church, and is now used as a burial-place by the Londonderry family.

Other abbeys there are none, save the poor little late Franciscan house of Bun-na-Margie, on the north coast, near Ballycastle, which however occupies a glorious site and has a romantic history.2 The Normans never attained a firm foothold in Leister, save in the strongholds of Downpatrick and Carrickfergus, and thus had no opportunities for founding houses suitable for the great religiousorders. The early Irish monastic system was quite different from the Norman, and had very few features in common with it.

F. J. B.

CASTLES.

Long before the raths or crannoges fell into disuse throughout our district, substantial castles were built of stone and mortar, particularly along the coast. Sir John de Courci, after his descent on the north-east of Ulster, promoted the building of strongholds in various parts of the country; and his numerous followers, anxious to secure the lands they had acquired by the sword, imitated the policy of their leader, and built castles upon their several estates in which to entrench themselves in those troublous times. A document of the time of Elizabeth, now in the British Museum, states that the principal means used to reduce Ireland were -- "By restraining and taking from the Irishry, by little and little, all trust of government: by building of castles and fenced houses, and committing the captaineries to trustie and well-affected English." And not only were castles built, but those who lived in them were obliged to keep them in repair. In the time of Richard II. it was ordered "that all who have castles or fortresses in Ireland should cause them to be repaired, and hold them in proper condition, and place therein a good and sufficient ward for their safe keeping."

This order was most cheerfully obeyed. It fitted in with most perfect harmony to the tastes of the barons and adventurers of the time; and the great number they built -- and they stud the land on almost every point of vantage -- together with the existing castles and strongholds of the Irish chiefs, speaks with no uncertain voice of the very lively times that existed, first amongst the Irish themselves, and then in the everlasting line of warfare that continued between the English to gain and keep, and the Irish to retain their own -- a state of affairs that continued for ages.

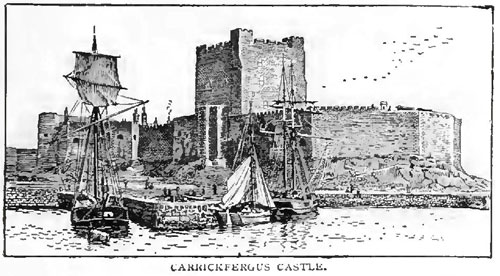

Of these martial strongholds the nearest to Belfast is that of Carrickfergus, which claims an unbroken line of military occupation from its foundation till the present day. This castle was built by Hugh de Lacy, and is erected on a basaltic dyke on the rocky shore; it had therefore the sea, which washed its feet, as a protection on half its circumference, and possibly had a moat on the land side. Its position was one of great strategic importance, and was the key to the north-east corner of Ireland; no invader could afford to pass it and thus destroy his base of action. A town soon gathered around it, and was ancient, or middle-aged, before Belfast existed or attained to the extent and dignity of a village. The history of this castle is full of stirring events and stormy vicissitudes, of capture and re-capture.

William III. landed close to this castle in order to commence his operations against James II. The spot is still shown.

The last episode occurred about a hundred and forty years ago, when the French, under Thurot, took the castle, plundered it, then demanded and received supplies from Belfast, and sailed away on the approach of the English reinforcements; but the triumph was short, and the "Mareschal" was taken off the Isle of Man. The attack on the castle was led by the Marquis d'Estrees, "who, seeing a child rush between the combatants, seized the lad, and breaking in a door with the butt end of a musket, placed the child in the hall of the house which happened to be that of the boy's own father, John Seeds, the Sheriff." The notorious privateer, Paul Jones, successfully attacked H.M.S. "Drake " off Carrick on 24 April, 1778. The castle is still regarded as of sufficient importance to receive a shot or two of blank cartridge during the annual naval manoeuvres.

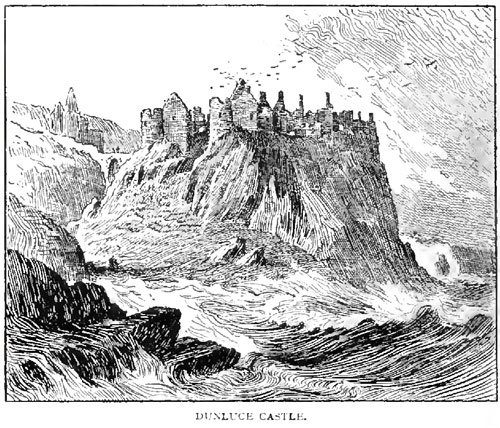

Next in point of interest is the picturesque ruin of Dunluce Castle, which forms a most attractive feature on the visitors' route to the Giant's Causeway. This castle has all the charm of romance about it, and like Mark's fabled castle in "Tintagil, half on sea, and high on land, A crown of towers," its striking picture is one not soon to be forgotten. A visit to it reveals the fact that, as well as a means of defence, there had also been an eye in its construction to comfort and luxury. It was on the last occasion when the great banqueting-hall was full of good cheer and hospitality that the kitchen toppled over into the sea, carrying some of the household with it; and this led to the abandonment of the castle as a residence by the Duchess of Buckingham, the widow of the Earl of Antrim. It is still the property of the MacDonnells, Earls of Antrim, who allow people to visit and inspect the home of their ancestors. The land-side buildings, occupied only in times of quietness, were walled in, and converged to a point at the drawbridge, which was spanned by a single arch over a deep chasm, all of which bears a remarkable likeness to a sketch of the entrance to the castle in Anne of Geierstein. The visitor should notice the banshee's tower, the old ovens, and the artificial channel on the north side, so that supplies could be taken in from the water side if the castle were hard pressed on the land side. From this waterway a natural tunnel runs to the lower level of the chasm above referred to.

It may not be uninteresting or out of place to notice here the small church a few hundred yards to the south of the castle, whose graveyard heaves with the mould of many noble but ill-fated sons of Spain, who perished in the wrecked galleons of the Armada on the stern headlands of this coast.

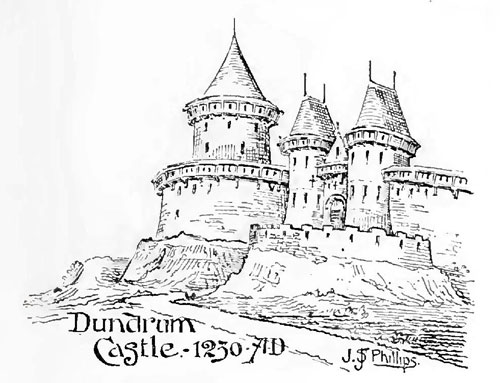

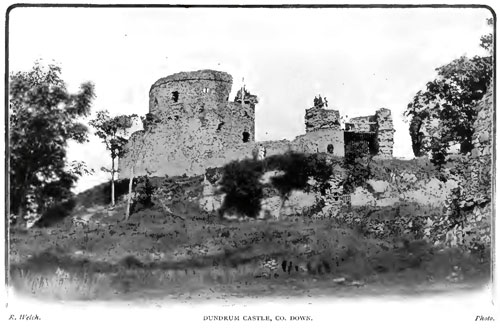

Dundrum Castle, Co. Down, built by Sir John de Courci for the Knights Templars, has a character of its own, defiantly Norman, and should be noted for this reason. Like many others it is well ruined.

The remaining castles are very numerous, and in every stage of decay and neglect. All of them are of great interest from the way in which their former greatness is woven into local history, and from their connection with the various Irish clans, and with English adventurers, but in size or martial construction they possess little that would arrest attention.

W. J. F.

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

Notes:

1. This is the Irish name for the Round Towers, and simply means "Bell Tower," another evidence of their Christian origin.

2. "Bun-na-Margie," by F. J. Bigger. Special Part of Ulster Journal of Archæology. M'Caw, Stevenson & Orr, Ltd., Belfast.